I was 8 years old when Pablo Escobar was killed.

The news had reported for weeks on the hunt for Escobar, but I was too young to really understand who he was or what he had done, just that he was a bad guy. When I saw footage of soldiers swarming around the scene of his death I thought “cool, they got the bad guy”.

It wasn’t until a few years later that I learned a bit more about Pablo, and Medellin, and cocaine, and realised that it wasn’t quite that simple.

It wasn’t until a few years later that I learned a bit more about Pablo, and Medellin, and cocaine, and realised that it wasn’t quite that simple.

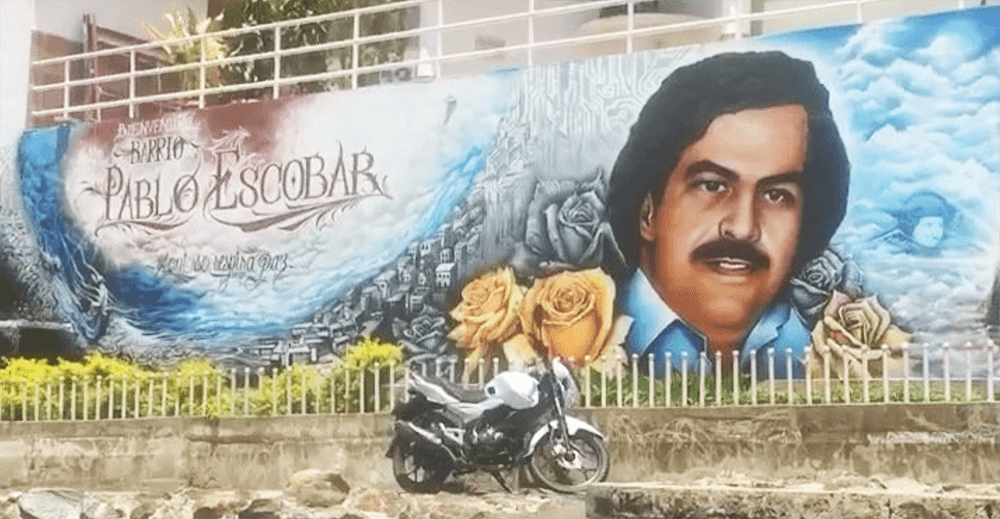

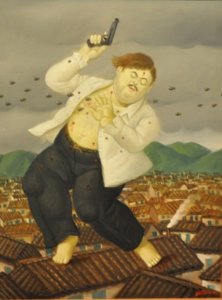

Pablo Escobar was a ‘bad guy’, but he wasn’t a purely malevolent force of evil. Sitting next to stories of airline bombings and judicial assassination campaigns there were tales of charity, of a ‘man of the people’ image carefully cultivated until it came crashing down so dramatically.

These two sides of Escobar could obviously never reconcile, and lead to a schizophrenic legacy (the documentary The Two Escobars shows this exceptionally well).

I also read stories of complicity, of governments and organizations willing to engage with the Medellin cartel, and those that followed. Unwilling or unable to fight them or stop their trade, ceding more and more authority to the cartels to try and avoid chaos, making a devil’s bargain. A ‘Pax Narcotica’.

As I got older and learned more about the drug trade, I saw that this bargain was being made at every level, in every location, along the supply chain. Sinaloa, Helmand, Laos, the street corner of almost every city in the world, and everywhere in between, the drug trade is so intertwined with government, commerce, and society that separating them becomes impossible, more akin to removing a malignant tumor than uprooting a weed.

It saw that the War on Drugs was not a black-and-white conflict, rather a shifting mosaic of greyscale. Those involved in the conflict are not simply ‘good guys’ or ‘bad guys’, they are pragmatists, opportunists, idealists, soldiers in a battle that stretches far beyond their corner, or patrol route, or their crop fields, their choices wreaking havoc and misery in places they will never see, and places they call home.

The effects of narcotics last long after they have been snorted or smoked. At every point in the supply chain decisions are made that have consequences on countless other parts of society and individuals, a million neurones spreading out of the spine. So why is it that videogames, traditionally so effective at building worlds of moral choice and consequence, have never embraced this theme?

In games, the drug trade always feels isolated, and temporary. You deliver a satchel of heroin to an NPC, and the bag disappears. Mission Complete. But where has it gone? How many users will that bag serve? How many will OD on the new package because they don’t know how strong it is? How does a neighbourhood respond to the deaths? How can the city find funds to fight the epidemic? How do the schools handle a slashed budget? What happens to the kids they should be teaching?

What happens when there is no solution to a problem, only a succession of impossible choices?

These are all questions that deserve answers, but there are none. There are only consequences, one cog turning another.

Developing Pax Narcotica: The Line has been about identifying these cogs and building them into the world as accurately as possible, to let the stories tell themselves. We do not want to moralize, or glorify, or pretend that we have any answers. All we can do is ask the questions.

As we continue development we will post more about the mechanics of Pax Narcotica: The Line, and what the player can expect. We will show trailers, explain design choices, respond to any feedback, and show you why this game needed to be made. We hope you will agree.

“No society can understand itself without looking at its shadow side.”

– Dr. Gabor Maté